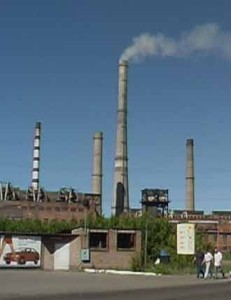

Ust-Kamenogorsk is one of Kazakhstan’s major industrial centers, and simultaneously one the republic’s most environmentally hazardous cities. In recent years, the city has been literally “suffocated” by its environmental problems. The chief culprits are industrial enterprises that continue to make use of obsolete technology and equipment, and who economize on environmental protection.

In the near future, interruptions in the city’s central heating system may be added to the residents’ other misfortunes. Heat is provided from Ust-Kamenogorsk’s Thermal Power Plant, which recently became the property of the American multinational energy company AES. Over the many years of the power plant’s existence, its old ash pits had become filled to overflowing, and an acute need arose to construct a new one. Already in 1985, an old clay quarry in a densely populated neighborhood on the outskirts of Ust-Kamenogorsk had been proposed as a site for a temporary ash pit. Even then, that area was considered environmentally hazardous, famed for such “points of interest” as a railway, the tailings pile from the Ulbinsk Metallurgical Factory, and the KazZinc industrial complex. Therefore, the local population spoke out categorically against the appearance of yet another dangerous neighbor, and no ash pit was constructed in the quarry.

Three years ago, however, company began construction, without informing local residents, without holding public hearings, and without observing even the simplest environmental, sanitary, and construction requirements. In order to expand the ash pit’s area, the power plant’s new owners, using all proper and improper means, obtained permission to reduce the pit’s sanitary zone from 500 meters to only a few meters. During the driving of piles, more than 140 homes suffered from the powerful vibrations. For the losses inflicted on them, only 38 individuals received a few crumbs of compensation—10,000 tenge (US $65) each.

In addition to residential homes, schools, a blood transfusion station, and a tuberculosis dispenser are located in direct proximity to the ash pit. The widening and deepening of the pit has also threatened the safe passage of trains along the rail line from Ust-Kamenogorsk to Barnaul. However, both the power plant’s owners and the pit’s designers assert with one voice that the pit presents no danger whatsoever.

Having failed to reach an understanding with the authorities, residents were forced to turn to the deputies on the city council, to the Committee on Environmental Issues in the Mazhilis (the lower house of Kazakhstan’s Parliament), and, finally, to the courts, in order to defend their constitutional rights. Their efforts, however, have been unsuccessful.

The management of the power plant insists that there are no alternatives to constructing the ash pit in the quarry, in spite of the fact that other options were already proposed fourteen years ago. Everything depends on what is understood by an “alternative.” If citizens’ rights and freedoms are the priority, and not the obtaining of profit through the humiliation and devastation of people, the destruction and pollution of the environment, then there is always an alternative.

From the video collection of the Ecological Society “Green Salvation”; photos by Sergey Solyanik and Denis Kopeikin.

Translation by Glenn Kempf